MUSCLEBOT - Adding muscles to a cobot in human robot interaction

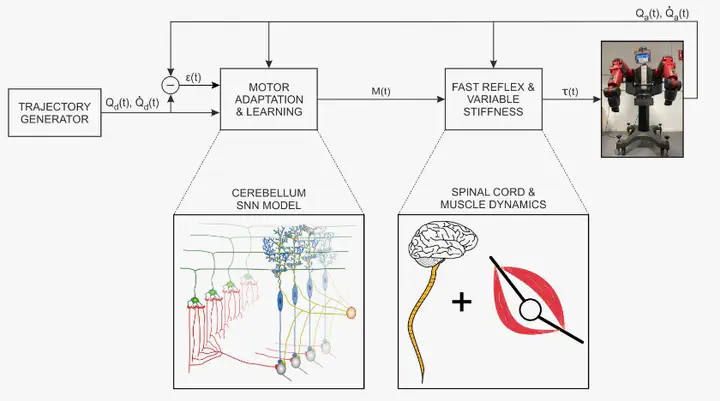

The Spino-Cerebellar control loop activating muscle pairs allows switching between admittance and impedance HRI. Synaptic adaptation slowly occurs within the cerebellum, thus allowing motor control adaptation. Conversely, fast reflexes are caused by the spine actuation under sudden moves, which takes advantage of muscle co-contration and helps varying the robot stiffness.

The Spino-Cerebellar control loop activating muscle pairs allows switching between admittance and impedance HRI. Synaptic adaptation slowly occurs within the cerebellum, thus allowing motor control adaptation. Conversely, fast reflexes are caused by the spine actuation under sudden moves, which takes advantage of muscle co-contration and helps varying the robot stiffness.

Robotics Paradigm in Human-Robot Interaction

During the last decades, a new robotics paradigm emerged, driven by physical human-robot interaction (HRI) and the utilization of collaborative robots (cobots) equipped with low-power motors and elastic components. In this context, controlling the cobot motion stiffness stands out as a promising approach.

- A low stiffness is akin to an admittance controller, excelling in soft environments but exhibiting contact instabilities and poor robustness in rigid environments.

- Conversely, high stiffness motion, comparable to an impedance controller, performs well in rigid environments but lacks accuracy in softer settings, allowing cobot intention to prevail over disturbances. Switching between these scenarios (admittance vs. impedance) is deemed convenient in robotics based on the HRI use case requirements.

Human beings naturally cope with this switching scenario through the natural co-contraction of muscles, typically arranged in agonist-antagonist pairs. This muscle co-contraction is finely shaped by spinal cord circuitry, driven by cerebellar motor control, enabling the learning of different stiffness musculoskeletal profiles.

For collaborative robotics to thrive in HRI, cobot performance should emulate the adaptability and flexibility of human behavior. HRI demands the cobot to perform with accuracy and control over movement execution. Therefore, in contrast to classic position controllers, torque control emerges as a more suitable solution for HRI, closely resembling human-like behavior.

Human behavior, in turn, is sustained by both hardware and software: the biomechanics of the musculoskeletal system, coupled with spino-cerebellar motor control, allows us to interact with others and the environment.

Hardware Side

On the hardware side, cobot design increasingly mimics the dynamics of living beings, incorporating springs as muscles and cables as tendons. To ensure compliance and safety, low-power motors and elastic components are employed to mitigate the consequences of possible impacts and facilitate HRI. This construction offers passive intrinsic compliance, contrasting classic rigid-bodied robots. Deformable bodies potentially provide more adaptation, sensitivity, and agility. However, the use of these hardware components comes at a cost: they hinder the applicability of traditional torque control methods due to the introduced nonlinearity in the cobot’s dynamic model, making it mathematically intractable.

Software Side

On the software side, studying and understanding different spino-cerebellar areas and their computational replication can expand the family of controllers providing adaptive, compliant robot control. Coping with this new hardware demands new control strategies, specifically adaptive torque controllers that do not rely on dynamic model availability and can handle physical nonlinearities.

MUSCLEBOT aims to benefit from decades of neuroscience studies about the spino-cerebellar structure and functioning. This approach involves adding muscles to a cobot, performing spino-cerebellar control capable of learning different HRI stiffness profiles.